Scientists say it wasn't inbreeding

New research suggests some catastrophic event, such as a natural disaster or virus, wiped out the world's last known population of mammoths on Wrangel Island.

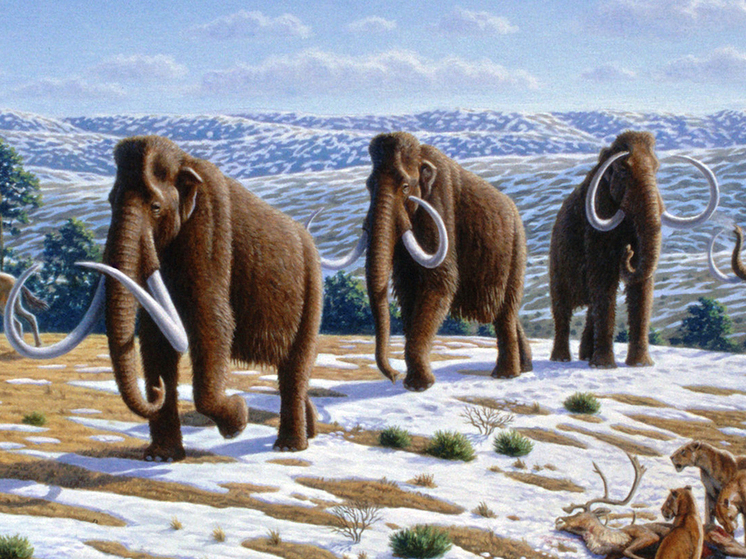

Photo: Public Library of Science < p>About 10 thousand years ago, a small group of woolly mammoths found themselves on an island off the coast of Siberia. While their mainland counterparts disappeared, this isolated herd multiplied. They became the only surviving representatives of their species and flourished for about 6 thousand years until they too became extinct.

Photo: Public Library of Science < p>About 10 thousand years ago, a small group of woolly mammoths found themselves on an island off the coast of Siberia. While their mainland counterparts disappeared, this isolated herd multiplied. They became the only surviving representatives of their species and flourished for about 6 thousand years until they too became extinct.

But what killed the last known population of woolly mammoths? Some had previously suggested that inbreeding destroyed the Wrangel Island colony. But new research suggests otherwise.

According to a new analysis, the Wrangel Island mammoths did have low genetic diversity, and some of the creatures suffered from genetic diseases, but that is not what killed them.

“We can show that in all likelihood, inbreeding and genetic diseases did not led to a gradual decline in the population towards extinction, explains evolutionary geneticist Lav Dahlen. “The population felt good, despite inbreeding.”

Scientists came to this conclusion by analyzing ancient DNA. The team studied the genomes of 14 people who lived on Wrangel Island between 4333 and 9219 years ago. They then compared them with the genomes of seven mammoths that lived on the Siberian mainland until 12,158 years ago. Collectively, the 21 genomes gave them insight into about 50,000 years of genetic history.

Although geneticists discovered that the mammoths that lived on the islands had acquired some minor genetic mutations, any abnormalities that could cause serious problems were gradually eliminated from the population. As a result, these mutations could not lead to the extinction of the species, according to the researchers. This is most likely due to the fact that the affected individuals were unable to reproduce.

Even if we exclude mutations as a result of inbreeding, experts cannot determine exactly what led to the death of the mammoths on Wrangel Island. Humans were most likely not responsible for this, as they did not appear on the island until 400 years later. But the team speculates that the creatures died in an accident — perhaps due to a new virus or a natural disaster such as an arctic volcano eruption or a fire in the tundra.

“It was probably just some kind of a random event that killed them, and if this random event had not happened, we would still have mammoths today,” the researchers suggested.

Woolly mammoths once roamed throughout North America, Europe and Asia. But about 15 thousand years ago, these giant creatures began to disappear — due to human hunting and habitat loss due to natural climate change. One group ended up on Wrangel Island, which was cut off from the Siberian mainland due to rising sea levels caused by melting glaciers.

Their isolation turned out to be a blessing in disguise. There were no predators, including humans, or other grazing animals on Wrangel Island, which gave the woolly mammoths carte blanche. In just 20 generations, the colony grew from eight breeding individuals to 200–300 mammoths.

“Wrangel Island was a wonderful place to live,” says Lev Dalen.

According to the geneticist, life on the islands was not so good because, without access to other herds, the isolated woolly mammoths engaged in inbreeding. Due to low genetic diversity, individual mammoths suffered from hereditary diseases. Since there were no predators on the island where they lived, they were able to survive despite their poor health until some catastrophic event occurred that ultimately killed them.

Even minor ones Genetic mutations could make woolly mammoths less resilient to other threats, such as climate change or disease.

«This is a really strong argument against the genetic decay model, but it doesn't rule it out completely,» says evolutionary biologist Claire Yuan.

More broadly, however, the findings could be useful to modern conservationists as they try to save endangered species. When considering how to help populations recover, genetic diversity should be a priority, according to the researchers.

“Mammoths are an excellent system for understanding the ongoing biodiversity crisis and what happens genetically when a species passes through a population bottleneck,” says evolutionary geneticist Marianne De Hask.

Свежие комментарии